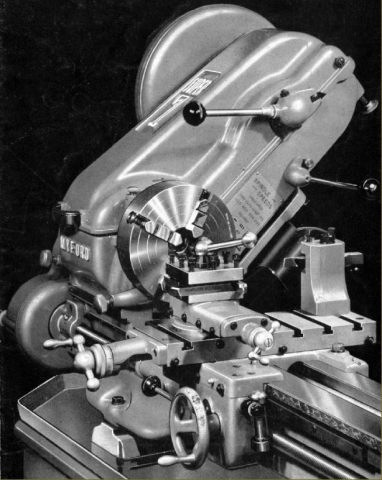

When, in September 1934, Cecil Moore founded the Myford Engineering Company and rented a spare room in a 5-storey lace mill in Beeston, Nottinghamshire (the address in the early sales sheets was given as Neville Works) few could have foreseen the day when, ten years later, he was to occupy all but a fraction of the same building and to continue trading, as the same company, until August, 2011. The foundation of this success - and the rise of Myford to pre-eminence amongst the then many competing makers of small lathes - was a range of just four machines: the very similar ML1, ML2, ML3 and ML4. Neat, compact and of appealing appearance all were designed and priced to appeal to the amateur market. However, despite their success, not even the most enthusiastic of owners could boast of them as state-of-the-art products and, by the close of the decade, the new-for-1937 American Atlas 6-inch (with its all-V-belt drive countershaft, roller-bearing headstock, fully-guarded changewheels and a host of user-friendly details) was setting the bench-mark for hobby-lathe design. In response, and designed during the closing years of WW2 (1939-1945) by Ted Barrs**, Myford launched what was to become the most popular and sought after small lathe in the UK, the ML7.

Undoubtedly drawing some design influence from American Atlas machines (including the 10-inch) the ML7 was announced to the press in February, 1946 with the first catalogue stamped "Provisional" and printed in the same A5 landscape format used for ML2 and ML4 publicity material; the cover was dark-blue with the single word "Myford" picked out in gold and in the company's traditional script. The pages were typed, reproduced on a Gestetner, and contained just one photograph showing the lathe mounted on its special "octagonal-form" braced sheet-steel cabinet stand. The first proper, fully illustrated catalogue was issued in October, 1947 and contained not only a complete technical specification but also cut-away diagrams and a list of the many and varied accessories.

From the start of production the ML7 was designed to accept a variety of profitable accessories (all listed and illustrated in the first full catalogue dated October, 1947) and very soon, with such an expandable and properly-engineered English small lathe on offer for the first time, many ex-service men (with gratuities burning a hole in their pocket) caused a lengthy waiting list to develop. The works prefix for the ML7 was "K" - with other contemporary designations including the ML.5 Capstan lathe being found as both the "F" and "R", the M.U. capstan as the "G", the M.L.6 capstan as "H" and the Myford/Drummond M-Type as "J". By the early 1950s, with just the ML7 in production (though a popular cylindrical grinder, the first of many, had also been introduced), it was decided that the market could stand the addition of a significantly altered and more highly developed lathe. Thus, in late 1952, the Super 7 was launched (with the provisional catalogue dated November of that year) - a machine that was able to accept all existing ML7 accessories.